King Vikramaditya in Jain Literature

Dhruti Ghiya Rathi

The immense details included in the Jain literature record the Jain principles and values which were followed by innumerable people. We need to recognize the contribution of our Acharyas who have carefully maintained the literature over generations, possible only with the support of illustrious kings like Emperor Vikramaditya and the supportive Jain community.

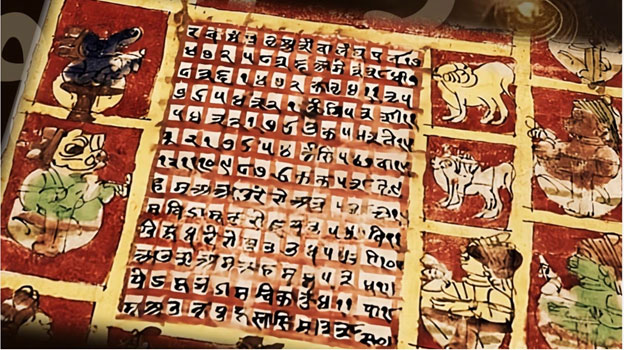

A new Chaitra based Vikram Samvat of Hindu Calendar year, recently started in March. Vikram Samvat, believed to be based on King Vikramaditya, is a historical calendar system used by most Indians since about two millenniums. Copper plate grants, idols, coins and even our Indian Constitution used Vikram Samvat (57 BCE) to record events. Despite that, some scholars have questioned the existence of King Vikramaditya.

What is King Vikramaditya’s relation with Jainism? Why was his era adopted and what are the values that made him an immortal personality? Answers to some of these are found in the Jain texts.

Adoption of Vikramaditya’s rule as a time marker, lies much in his generosity, and a presence over vast part within and outside India. In the first article, Dr. Dhing clearly points to Emperor Vikramaditya’s dedication towards a fair and just rule, his generosity, and charitable work, as some of the reasons why his era became so widely accepted as indian historical marker. The commemoration of his rule by the Indian Postal Service with a colorful postage stamp speaks to the acceptance of him as a historical personality, having references in various Indian literature.

The story about Kalak Acharya in Kalakacharya Kathanak, part of Kalpasutra Jain text, is fundamental for understanding the existence of Emperor Vikramaditya and the arrival of the Sakas. Sten Konow states:

“Shortly after the death of Mithradates II (88 BCE), the Sakas of Siestan made themselves independent of Parthia and started on a career of conquest, which took them to the Indus country. Later on, about 60 BCE the Sakas had extended their dominion to what the Kalakacharya Kathanak calls the Hindukadesh i.e, the Lower Indus country, and thence to Kathiawar and Malav, where they probably introduced the national era. In 57/56 BCE, they were here ousted by Vikramaditya, who celebrated his victory by establishing an era of his own, which we, 70 years later, find use in Mathura.”

However, in our second article, eminent author Devdutt Pattanaik considering Kalakacharya Kathanak as a mythology and a folklore, elaborates on the same. He also rightly questions the need to attach the story of Kalakacharya Kathanak to the Kalpasutra text. Perhaps, the fifty plus texts found in Jain literature, majority of them written by Jain Acharyas, speak to the importance of King Vikramaditya and Kalak Acharya in Jainism. Kalakacharya Kathanak includes a change of date in the Paryushan, which is a major change to the important Jain festival, hence finding the need for it to be documented in a text that is always read during Paryushan.

Whereas, in the third article, Acharya Jinottam Surishavrji illustrates the story of Emperor Vikramaditya. Based on Prabhavak Charitra and Prabhandha Kosha, one finds various snippets of Vikramaditya’a life and character, and an older brother Bhratihari, both sons of King Gandharvasena. In this regard, Sagarmal Jain comments that Bhavishya Puran and Skanda Puranas also mention his brother as Brathihari. We see examples of writing, usage of Prakrit and Sanskrit languages. episode of Siddhaasena Diwakar desiring to convert Jain Ardhamagadhi Prakrit texts to Sanskrit, and his first conversion of Namokar Mantra to Sanskrit as “Namo Arhat Siddhacharya Upadhyaya Sarva Sadhu bhya”.

Next article provides information about Avanti Parshwanath temple in Ujjain, also known as Mahakal. This temple is mentioned in Kumarpal Pratibodh, written around the time of Hemachandra Acharya, and in the records about Vikramaditya and Siddhasena. Kalyan Mandir Stotra, composed in this temple by Siddhasena in praise of Parshwanath and which led to the appearance of idol of Avanti Parshwanath is also included.

In the fifth article, Rahi Shah and Janvee Patel find doing “Daan” and helping others infectious, as gleaned from their experience about serving hot meals. Acts of generosity was a virtue that made Vikramaditya immortal. Vikramaditya’s generosity and his favours towards Jain religion is found in Prabhavak Charitra, mentioning a Jirnodhar (refurbishment) of a temple by Jivadevasuri. The funds of which were provided by Mantri (minister) Limba, in Vikramditya’s 7th year of rule. The influence of Jain values on Vikramaditya as well as the Sakas brought in by Kalak Acharya who were later ousted from Ujjain, but who ruled Gujarat over a long period of time cannot be hidden. We find Saka Satraps using Jain terms such as Kevalgnan Sampraptanam, as found in Junagarh rock inscriptions, and recorded in Anitquity of Kach and Kathiawar and Historical Inscriptions of Gujarat. Jainism has given tremendous importance to Daan, as seen in Rahul Kapoor Jain’s video based on Tattvarthasutra.

In the last article, Sravani Sarkar finds reason to consider King Vikramaditya as a historical person based on numismatic evidence.

Literary evidence of King Vikramaditya’s reign can be known from King Salivahan or Shalivahan in Jain texts, whom Brown and many others consider same as King Satavahan ruling from Paithan, Maharashtra. Vikramaditya and Salivahan were involved in a war along the Narmada River. A coin of the Satavahana (Salivahan) prince Saktikumara, has been reported by Ajay Sastri as a stratified find from Andhra Pradesh. Raychaudhari considers Saktikumara as son of Salivahan, based on Jaina literature. This makes Satakarni I father of Saktikumar, likely the same person as Salivahan of Jaina literature. Satakarni I was known as Dakshinadhipati. Lord of the South, which is plausible, because of his relationship with his father-in-law King Samprati of Ujjain, who conducted the Bhagwan’s Rath yatra to Sri Lanka per Zaveri.

Also, his descendant Hal Satavahan created Gatha Saptashati in Prakrit around 1-2CE, per V Smith, Brown and Sagarmal Jain. Hal expresses donations in lakh (hundred thousand) by King Vikramaditya to his servant, hinting to the invention of zero by then, as well as expressing the magnamity of Vikramadiyta. Sagarmal suggests that Vikramaditya had already deceased by then. Hence, clearly the Jain texts cannot be talking about King Chandragupta II Vikramaditya of the Gupta dyansty or later Vikramadityas, who likely added the epithet Vikramaditya as a suffix to their name, desiring to emulate the fame of a prior globally known personality such as that of Emperor Vikramaditya.

Multiple references in published and unpublished Jain literature, and other sources regarding King Vikramaditya, should thus be re-examined by historians to consider Emperor Vikramaditya as a historical figure of India, who played an important part in building the fabric and ethos of India and Jainism, and whose values and the time of reign are valid even today for the larger population of India.

Hope our readers catch the infectious desire of undertaking humanitarian and literary causes, carrying forward the torch of King Vikramaditya’s way of upholding and living the Jain principles in the present Vikram Samvat 2080 or Gregorian year 2023.