Introduction

Jainavenue is a medium to serve the spiritual path of Jainism

Many Views, Many Truths, One Truth A Jain-Inspired Approach to the Diversity of Worldviews

March, 2022 by Dr. Jeffery D. Long

Background and Context

I have reached a point in my career at which I can never be sure, when I give a presentation, how familiar people are either with me or with my work. To those of you to whom all of this will be brand new, welcome! I hope you find what I have to say interesting and engaging. To those of you who have heard some or all of this material previously, my sincere apologies!

When discussing a controversial topic like religion, I find it is always helpful to be clear to one’s audience what one’s perspective is and where one is coming from before launching into the material itself. I was raised a devout but independent-minded Roman Catholic and grew up in a small town in Missouri. When I was ten years old, my father suffered a debilitating injury from a truck accident. The suffering he experienced prompted him to take his own life two years later. It was from these experiences that my lifelong interest in religion and philosophy emerged. I began a search for answers to the big questions in life and felt I should cast as wide a net as possible, not only studying the teachings of the tradition in which I was raised, but a diverse range of religions and philosophies; and I found much that was wise and true in every tradition that I studied.

I was particularly drawn to the traditions of India. In contrast with the view, I found among many in my small-town community that only one religion will lead its followers to eternal life, the others being condemned to eternal damnation, I took great comfort in the words of Gandhi:

Religions are different roads converging upon the same point. What does it matter that we take different roads so long as we reach the same goal? In reality there are as many religions as there are individuals. I believe in the fundamental truth of all great religions of the world. I believe that they are all God-given, and I believe that they were necessary for the people to whom these religions were revealed. And I believe that, if only we could all of us read the scriptures of different faiths from the standpoint of the followers of those faiths, we should find that they were at bottom all one and were all helpful to one another.1

And in the words of Sri Ramakrishna:

I have practiced all religions–Hinduism, Islam, Christianity–and I have also followed the paths of the different Hindu sects. I have found that it is the same God toward whom all are directing their steps, though along different paths. He who is called Krishna is also called Shiva, and bears the name of the Primal Energy, Jesus, and Allah as well–the same Rama with a thousand names.2

God can be realized through all paths. All religions are true. The important thing is to reach the roof. You can reach it by stone stairs or by wooden stairs or by bamboo steps or by a rope. You can also climb up a bamboo pole…Each religion is only a path leading to God, as rivers come from different directions and ultimately become one in the one ocean… All religions and all paths call upon their followers to pray to one and the same God. Therefore, one should not show disrespect to any religion or religious opinion.

My journey eventually led me to take dīkṣā (initiation) in the Vedānta tradition of Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda: a tradition committed, at its core, to religious pluralism–the belief that truth can be found in many religions and philosophies and realized through many spiritual paths.

When I took up the study of Indian traditions as my professional path, I found that this idea of religious pluralism was not well regarded in the academy. Religiously conservative scholars objected to the idea of many true and valid paths, and more secular scholars felt this approach lent itself to a simplistic and superficial understanding of religious traditions in all their rich difference and variety.

While I found many of these objections to be legitimate, I nevertheless remained convinced that religious pluralism expressed an important truth: that there is wisdom to be found everywhere, and that the best approach to differences in worldviews is to seek to learn what one can from each perspective and integrate the insights of many views into one’s own, thus advancing towards truth.

I also found, as I was exploring the philosophical traditions of India, that the tradition which seemed to have formulated this insight with the greatest logical precision was the Jain tradition. It was in Jain philosophy that I found the conceptual tools for expressing pluralism such a way as to address the objections that contemporary scholars had launched against this position.

In the meantime, as both my life and my career have unfolded, I have witnessed the world descend ever more deeply, it seems, into the darkness of violence and inter-religious conflict. It is my view that religious pluralism is not only an important position because it is intrinsically true, but also because humanity desperately needs to find a way to appreciate difference, even on such topics as dear and central to our self-understanding and sense of well-being as religion. The single greatest threat to humanity, and all of life on earth today, is, I think, climate change. Religiously based conflict, however, is a close second, and is in fact intertwined with the ecological crisis. If we feel empathy and compassion for our neighbors, it is more likely that we will work together in the face of ecological catastrophe and manage to survive, and perhaps even flourish. But if we have already been divided by religious and other ideological disagreements to a point where we do not see one another as fully human, then the struggle has already been lost.

It is from this background and perspective that I now turn to the question of how to think about religious diversity and the conflict of worldviews.

Why Are We So Violent?

“Why,” we often ask ourselves, “is there so much conflict, so much violence in our world, especially in the name of religion?” Each of the major world religions includes some variation of the famous Golden Rule: the principle that we all should treat others as we wish to be treated. Yet it is the rare religious tradition that has never, at any time in history, been used as a justification for violence against those who are regarded as other: the heretic, the heathen, or the infidel.

Some would argue that all this irrational violence, violence which goes against the central ethical insights of the traditions in the name of which it is committed, is a reason to reject religion altogether: that adherence to beliefs which are incapable of scientific verification does not belong in a society that wishes to regard itself as advanced or enlightened.

The irrationality of religiously motivated violence–its self-contradictory and self-negating character–can be traced, according to this line of thought, to the irrationality of religion itself. If this root cause of violence could be eradicated, so the argument goes, violence itself would subside, and we could all share a more peaceful and habitable world. In the words of one of my favorite artists, John Lennon, “Imagine no religion.” Indeed, religion has become a dirty word in many quarters, even among those who find much wisdom in the world’s religions, and who prefer to call themselves ‘spiritual but not religious.’ Religion is simply equated with bigotry and fanaticism.

Are matters really this simple, though? One of the lessons of the twentieth century should certainly be that ideologies rooted in the rejection of religion are no less capable of inhumanity, and of violence on a massive scale, than are religious ideologies. Indeed, when coupled with the capabilities of modern technology, the violence undertaken in the name of non-religious ideologies like Communism and Nazism has in fact taken far more life than pre-modern history’s witch-hunts, crusades, and inquisitions. Think of the Holocaust, or the Killing Fields of Cambodia, which lost one fourth of its population in a frenzied mass murder carried out in the name of an anti-religious political ideology.

The evidence, therefore, would suggest that it is not religion, specifically, that is at the root of violence. Any ideological difference, any difference of worldview, can be marshaled in defense of the notion that we ought to kill one another. And we can also observe many historical situations in which there have been diverse religions and this diversity has not been accompanied by violence or persecution. Religious difference by itself is an insufficient explanation for violence undertaken in its name.

Regarding violence in the name of non-religious ideologies, we are again faced with deep irrationality; for, like the religions of the world, some of the non-religious, secular ideologies that have served as rallying cries for slaughter are, like the world’s religions, rooted in humane ethical visions. Marxism is not rooted in a desire to foment violence, but the desire to ensure that resources are distributed in an equitable fashion–certainly a noble end, with which many religious persons agree (as the Dalai Lama agreed with Mao, before he realized what Mao had in mind for Tibet).

If it is not the religious or non-religious character of a worldview that renders it a possible justification for violence, there must be something additional, something that is projected onto a worldview which distorts it, turning it into something it was not originally intended to be. The modern Hindu sage, Swami Vivekananda, claims that the source of inter-religious violence (and we could add, violence across worldviews more generally) is not the worldviews themselves, but rather a set of attitudes that become entwined with them. He defines these as sectarianism, bigotry, and fanaticism.4 Broadly, these three could be defined, respectively, as the tendency to fragment a community because of differences in views (rather than striving for co-existence), a tendency to dislike others because of their worldview, ethnic or national origin, gender, or sexual orientation, and a way of adhering to one’s worldview that precludes appreciation for other views. The danger, the seductive power, of these destructive tendencies lies in the fact that, when one succumbs to them, one feels that one is in fact behaving righteously, that one is being faithful to the values that one’s tradition upholds.

The tragedy is that in so doing one is actually betraying those very values by embarking on a slippery slope which may lead to hating and killing one’s neighbor in the name of a tradition that teaches one to love one’s neighbor as oneself. One of the great frustrations I have experienced in engaging with people of all religions over the years is the tendency to identify the intensity of one’s devotion to a tradition with the extent to which one becomes unhinged and irrational when talking about it. A fanatic is not more devoted to his religion than a so-called ‘moderate.’ It is, in fact, likely that the fanatic has not understood the deeper nuances of being committed to a view while simultaneously showing respect for other views, even those which may appear to be opposed to it, while the moderate sees such respect as a duty that follows from one’s religious commitment.

Why, again and again, do we succumb to these tendencies–these pāpa saṃskāras, or evil habits, as they are called in the Sanskrit language of the spiritual and philosophical traditions of India? The thread underlying this unholy trinity of sectarianism, bigotry, and fanaticism, it seems, is fear: fear that the other will undermine our precious values, or that the other will take resources from our community, or that the other is in fact evil and means to do us harm.

According to the traditions of India, this fear is itself rooted in a deeper ignorance, which is really the root of all the evil in the world. One might ask, “Ignorance of what?” The answer is, “Ignorance of our true, spiritual nature, and the ways in which this nature binds us to all beings.” We are all, ultimately, one. Each of the Indian traditions has its own way of expressing this unity. In the Hindu philosophy of Vedānta, the term for this basic unity is Brahman, the infinite existence, consciousness, and bliss–anantaraṃ sat-chit-ānandam–that is the essential nature of all beings, and manifests in each of us as our Ātman, or fundamental Self. The Buddhist traditions speak of Interdependent Origination, or Interbeing–pratītya-samutpāda–the basic interconnectedness of all beings. The Jain tradition speaks of the universal reality of the Jīva–the life force, or soul, which is the essential nature of all living things.

Our violence against the other is made possible by our seeing the other as wholly other: as so other that we are blinded to the ways in which we are the same. As the Western philosopher Spinoza observed, our love for others tends to diminish to the degree that they are different from us. At one extreme end, there is the psychopath, who has no regard for the well-being of anyone other than himself. Fortunately, such persons tend to be quite rare. But it is all too easy for many of us to withhold our love from those whom we do not know–people outside of our immediate community of daily interaction. It is even easier for us to withhold our love from people who hold a different worldview, who speak a different language, or who have a different physical appearance from ourselves. It is even easier yet to withhold our love from living beings that are non-human, and thus to inflict violence which we would never consider inflicting on our fellow human beings, including consuming them as food. In fact, the ease with which we inflict violence on non-human life is a template for our violence against one another; for our violence against our fellow humans is facilitated if we can regard them as non-human: as animals. It is not uncommon to hear enemies in a conflict described as ‘animals.’ I recall my father, a veteran of the Vietnam War, describing how, in his military training, he was discouraged from thinking or speaking about the Vietnamese people as human beings. The soldiers were instead conditioned to refer to the Vietnamese people only with derogatory ethnic slurs meant to render them less than fully human in the soldiers’ minds.

In the act of “otherizing” the other–that is, of attending only to the ways in which the other is unlike ourselves and projecting onto the other only the traits we do not wish to see in ourselves– we commit, one could say, the original violent act. On the basis of this otherization, this literal alienation, progressively greater violence becomes possible. One could say that from bigoted and hateful thoughts flow bigoted and hateful words; and similarly, from bigoted and hateful words flow bigoted and hateful actions.

At the same time, valuing otherness negatively, and focusing only upon the ways in which the other is like us, can also constitute a kind of violence. An example of this is the fallacy of “colorblindness,” in which we assert that we will simply treat everyone the same–perhaps the same as we wish to be treated ourselves. This sounds deceptively like the Golden Rule, except that by failing to attend to the ways in which others are, in fact, different from ourselves–culturally, for example–we may end up treating them poorly. It is necessary to deepen our understanding of the Golden Rule to mean not only treating others as we wish to be treated but treating others as we would wish to be treated under the same circumstances, with the same background of history and cultural assumptions: treating others as we would wish to be treated if we were them.

The Jain Philosophy of Infinite Diversity

This brings me to my central thesis, namely, that the Jain philosophy of infinite diversity, or anekāntavāda, can be of great assistance in cultivating empathy, nonviolence, and recognition of the common, fundamentally spiritual nature of every being we encounter, as well as a deeper appreciation for each being’s distinctive uniqueness. One can integrate the spirit of this philosophy into one’s life without necessarily adopting Jainism in its entirety, although it certainly does invite one to explore the rich, profound tradition in which it emerged.

What is the Jain philosophy of infinite diversity, and how can it help us to follow the middle path between seeing the other as wholly other–thus allowing the other to be an object of potential violence–and appreciating the other only in as much as the other is like us–thus allowing us to resist learning from difference and expanding our view of reality? How can Jain philosophy help us live peacefully with those who are different from us, yet share a common spiritual nature?

To understand the Jain philosophy of infinite diversity–or as I have also called it, the Jain philosophy of relativity–it is necessary first to understand some basic facts about the Jain tradition itself, as well as the broader Indian cultural milieu in which it developed and in which it has thrived for thousands of years.

The Jain tradition itself is truly ancient. According to Jain teaching, what we now call Jainism is as old as the universe itself, describing the nature of reality throughout all cosmic time. From a less philosophical, more historical perspective, some have argued that Jain practice can be traced to the Indus Valley Civilization, which was at its height from approximately 2600 to 1900 BCE. This is not a widely held view among scholars, given the lack of firm data about the culture of this ancient civilization, and the fact that we are not yet able to read its writing system, or even to know definitely which language or languages it depicts.

According to Jain teaching, this tradition can be traced to a series of twenty-four beings who have lived in our region of the universe over the course of our current cosmic cycle, a period extending back many millions of years. The stories of the lives of these founding figures, called Tīrthaṅkaras, is difficult to correlate with historical scholarship, but a number of them are attested in independent, non-Jain sources from ancient India: specifically, the twenty-fourth Tīrthaṅkara, Mahāvīra, who likely lived in either the fifth or sixth century BCE and who was a contemporary of the Buddha.

Mahāvīra, like Buddha, is not a family name, but a title. Just as Buddha means Awakened, Mahāvīra means Great Hero, and refers to the heroic effort required in the Jain path to freedom from the cycle of rebirth. Mahāvīra is also known as Jina, or Conqueror–a militaristic image, but one that refers to the conquest of one’s inner enemies, including the impulse toward violence. A Jaina–or Jain in contemporary Indian languages–is a follower of the Jina.

Jainism, Buddhism, and the dominant Hindu traditions of India all affirm that all living beings are far more than their physical bodies. We are spiritual beings, dwelling in a physical form that has been shaped by choices we have made while dwelling in earlier physical forms. When our bodies die, our essential spiritual reality continues in another form.

This process of rebirth is described in one of the Hindu scriptures, the Bhagavad Gītā, in the following way: “Never was there a time when I did not exist, nor you…nor in the future shall any of us cease to be. As the embodied soul continually passes, in this body, from boyhood to youth, and then to old age, the soul similarly passes into another body at death. The self-realized soul is not bewildered by such a change.”5

Becoming a ‘self-realized soul’ is the aim of all of these traditions (although the Buddhist tradition does not use the term ‘self’ in relation to this process, seeing it as carrying a residuum of egotism, a quality which all of these traditions aim to overcome). A self-realized soul is free from the cycle of death and rebirth, having learned the lessons that our experiences as embodied beings teach us. All of our choices–specifically, those infused with ego-based desire–lead to inevitable results. The principle of cause and effect that governs this process is called karma, which can be translated as action, or as work. One’s karma, one could say, is the work one has to do in one’s lifetime, the work one brings into one’s lifetime from one’s previous existence, and that one will carry over into other lifetimes until one has become free from it.

This freedom, or mokṣa–liberation from the cycle of rebirth–is the result of self-realization, or absorption in one’s true nature, also called nirvāṇa. This is the ultimate aim of Jain, Buddhist, and Hindu spiritual practice. Each of these traditions can be seen as reflecting different variations on this common theme, and as employing different strategies for realizing this common end.

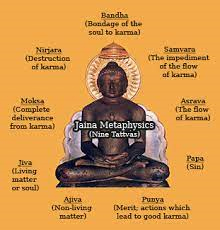

In the Jain tradition, the living being is known as jīva, which can be translated as soul, but literally means living being or life force. There are as many jīvas as there are living things: a number that is virtually infinite. Each jīva possesses four qualities to an infinite degree, which are therefore known as the ananta-catuṣṭaya, or the four infinitudes. These are infinite knowledge (jñāna), infinite perception (darśana), infinite bliss (sukha), and infinite energy or power (vīrya). As long as we are bound to the cycle of rebirth, though, we do not realize the infinite potential which these qualities reflect. This is because our jīva has been associated, for countless lifetimes, with ajīva, or non-living matter. Karma, according to Jainism, is a type of ajīva which adheres to the jīva as a result of the passions, or kaṣāyas that we feel when we have an experience.

Experiences are of three basic kinds: pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral. The kaṣayas which tend to correspond to these are, respectively, attraction, aversion, and indifference. The key to stopping fresh karma from entering one’s jīva is to cultivate a state of samāyika, or equanimity, whether one is experiencing something that is pleasant, painful, or neutral. Samāyika is not the same as indifference; for we feel indifferent to an experience only because we do not feel that it affects us. Samāyika is living in the recognition that the inherently pure, blissful nature of our fundamental self cannot be destroyed or disrupted, no matter what external circumstances we are experiencing. It is being ‘alike in pain and pleasure.’ This means that we do still experience pain and pleasure. But we do not allow them to overwhelm us. The distinction between equanimity and indifference is an important one. If we do not attend to this distinction, we may develop the false impression that we are to be indifferent to the sufferings of others; but this is the precise opposite of what the Jain tradition teaches. For an essential element in the cultivation of equanimity is the practice of ahiṃsā, or nonviolence in thought, word, and deed. The feelings that can drive us to desire harm for others attract the most destructive karmas to the soul. They need to be conquered if one is to experience the true, lasting peace of nirvāṇa. Ahiṃsā is the foundation of Jain ethics. The entire Jain way of life, right down to its strict vegetarian diet, is based on the ideal of ahiṃsā. Perfect ahiṃsā is impossible for householders–persons living lives fully engaged with society, and which involve earning a material livelihood and raising a family. The practice of ahiṃsā to the highest degree humanly possible falls to ascetics–Jain munis and sādhvīs, or monks and nuns. The image for which the Jain tradition is probably best known is of Jain ascetics gently sweeping the ground in front of them to avoid even accidentally treading on tiny organisms on the ground, and sometimes wearing a muḥpatti, or mouth-shield, to avoid ingesting them from the air. (I should note here that not all Jain ascetics wear a mouth-shield, and that even those who do, do not do so at all times. And there are some ritual occasions when householders wear them as well.)

It may be counterintuitive to claim that a tradition which enjoins such a strict way of life, seeing a thoroughgoing practice of ahiṃsā as essential to the attainment of spiritual liberation, possesses a philosophy of infinite diversity that can aid in an acceptance of all worldviews.

Why is this so? It is because one might expect Jains to assert that all other traditions fall short of the true practice of nonviolence, and so fail as paths to a higher spiritual state; and indeed, there have been Jains throughout history who have made such statements. Jain reflection on the nature of the jīva, however, has led to anekāntavāda, the Jain philosophy of relativity.

How did this remarkable development occur? Historically speaking, the earliest instance of this philosophy can be found in the Jain Āgamas, or scriptural texts, in which are presented the Jain community’s memory of the teaching of Mahāvīra himself.

In one of these scriptural texts, Mahāvīra responds to a set of questions posed by a disciple on the nature of the cosmos and the soul.

[T]he Venerable Mahāvīra told the Bhikkhu Jamāli thus:[T]he world is, Jamāli, eternal. It did not cease to exist at any time. It was, it is and it will be. It is constant, permanent, eternal, imperishable, indestructible, [and] always existent. The world is, Jamāli, non-eternal. For it becomes progressive (in time-cycle) after being regressive. And it becomes regressive after becoming progressive. The soul is, Jamāli, eternal. For it did not cease to exist at any time. The soul is, Jamāli, non-eternal. For it becomes animal after being a hellish creature, becomes a man after becoming an animal and it becomes a god after being a man (Bhagavatī Sūtra 9:386).6

Mahāvīra is here explaining that those who claim the cosmos is eternal and those who claim it is non-eternal are both correct, from different points of view. According to the Jain worldview, there has always been a cosmos. It is, in this sense, eternal. It is not, however, static. It undergoes constant change, its character being vastly different during the various phases of a cosmic cycle, known as progressive (or utsarpiṇi) and regressive (or avasarpiṇi). It is, in this sense, not literally the same universe from era to era. In a similar vein, the individual soul, or jīva, is also eternal. It has always existed and will always exist. It inhabits numerous forms, however, over the course of its journey to freedom. The same soul can be, in one lifetime, a human being, in another an animal, in another an entirely different kind of being altogether. These forms are not eternal. They perish and pass away, to be replaced by another, and another, and another until liberation is achieved. The answers to the questions, “Is the cosmos eternal or non-eternal?” and “Is the living being eternal or non-eternal?” depend upon whether the questioner has in mind the totality of the cosmos or its current state of affairs, or the jīva as such or the type of body it currently inhabits.

In this way, seemingly incompatible answers to these questions can both be seen to be true. There is that in all of us which is eternal, and that in all of us which will pass away forever. The two are not mutually exclusive.

This approach to seemingly contrary answers to the same philosophical question became, in the hands of Jain intellectuals over the course of two and a half millennia, a complex system of logic according to which the views of rival systems of thought could be reconciled into an integral synthesis.

One of the main debates among the various schools of philosophy in ancient India was over whether the essential nature of reality could best be described in terms of impermanent moments of existence or in terms of an eternal, unchanging reality on which the illusion of time and change is projected by the mind. Buddhist traditions tended to adhere to the first view. According to Buddhism, it is our attachment to entities that we falsely view as solid and permanent that is the primary cause of our suffering, and our bondage to the cycle of rebirth. Hindu traditions tended to adhere to the second view, holding that our true nature is infinite being, consciousness, and bliss, with no real differentiation and no division across time. It is our adherence to that which is impermanent and changing, in this view, that is the cause of our suffering and bondage.

Jain thinkers, with their both/and view of the nature of the jīva–as having a nature which is eternal and unchanging, but as also passing through various forms to which it is really and truly, and not only apparently, bound–asserted that the Buddhists and Hindus were both correct and both incorrect in the way they described reality. Buddhists, on the Jain understanding, rightly described the ephemeral nature of the phenomena the jīva experiences, and Hindu traditions such as Vedānta rightly described the eternal nature of the jīva’s essence. Each was false in as much as it denied the truth of the other view.

Reality, according to this Jain understanding, is complex. It possesses many sides or aspects, which is the literal meaning of anekānta. An Indian story often used to describe this view is the famous parable of the Blind Men and the Elephant (a story told by the Buddha to a monk confused by the many views he had heard debated among the followers of different sects).

The elephant has many parts–its legs, tail, ears, tusks, and so on. A blind man, grasping one of these and taking it to be the whole elephant, will argue with those who grasp other parts and describe the elephant in terms different from the first blind man’s experience. In this parable, the arguing blind men are the world’s religions–or even, we could say, all worldviews, religious and non-religious. Each religion can be compared to a conceptual matrix for grasping reality. A Christian has a positive experience and sees the grace of God. A Jain has a similar experience and sees the working of karma. A non-religious person has a similar experience and sees a lucky random chance. If we apply the Jain philosophy of relativity to these three seemingly incompatible views, we can see each as capturing a different part of the reality of the situation. Jain logic allows us to see differences not as conflicting, but as complementary.

Anekāntavāda is a metaphysical–what philosophers call an ontological–view. It is a view, that is, about the nature of reality. Corresponding to anekāntavāda is a teaching called nayavāda, the doctrine of perspectives. This extends anekāntavāda into the realm of what philosophers call epistemology–the study of knowledge. We know the nature of an entity based on which of its aspects we perceive. Each aspect corresponds to a point of view from which the entity may be approached. A worldview is a matrix for grasping reality and grasps those aspects of reality for which it is designed. Each worldview is a gateway to insight about a particular piece of the totality of being.

Corresponding to both anekāntavāda and nayavāda is a doctrine about how best to make assertions about reality on the basis of the pluralistic understanding of truth these two doctrines provide. This is called syādvāda, or the doctrine of conditional predication. Literally, syādvāda, means ‘the doctrine of syāt.’ Syāt is a word which, in Jain technical usage, means, ‘in some sense,’ or ‘from a certain perspective it is the case that…’ Recall Mahāvīra’s account of the eternality and non-eternality of the world and the soul. A claim about reality–its permanence or impermanence, its having one nature or another–are true or false depending on which aspect of reality it describes.

According to syādvāda, truth claims have seven possible values:

- In one sense, a claim is

- In another sense, a claim is

- In another sense, a claim is both true and

- In another sense, the truth of a claim is

- In another sense, a claim is true, and its truth is

- In another sense, a claim is false, and its truth is

- In another sense, a claim is true and false, and its truth is

These seven statements exhaust the possible non-redundant truth-values of a given claim.

Questions

The Jain philosophy of relativity raises a number of important questions which need to be addressed if it is to be utilized as a way of navigating diverse worldviews in a way conducive to peaceful co-existence.

The first of these is the question of radical relativism, which I define as the view either that there is ultimately no truth, or that the truth can never be known, or that the truth is whatever one wants it to be. This, in fact, was the chief objection raised against this philosophy by Buddhist and Hindu thinkers in ancient India: that saying the same claim can be both true and false is incoherent. If everything is true, then nothing is true, and one ends up finally unable to say anything.

It is especially important, I believe, in this era of ‘alternative facts,’ to clarify that the Jain philosophy of relativity is not, in fact, a radical relativism of this kind. Jainism operates from what philosophers call a realist ontology, affirming that there is an ultimate fact of the matter, or a way thing are. What the Jain philosophy of relativity does is to disambiguate or clarify metaphysical claims of the kind typically made in religious and philosophical traditions claims about the way things ultimately are. The substance of the Jain claim is that the way things are is complex and not reducible to any single concept. The ultimate fact of the matter is complexity. And even the concept of complexity does not fully grasp the nature of being, which is why, from one perspective, the nature of reality is said in the Jain tradition to be inexpressible: beyond what limited words and concepts can encompass. Ultimate reality can thus be viewed as both process and substance, as both personal and impersonal, as neither, nor so on, depending upon the perspective one takes.

This is not the same as saying reality is whatever one wants it to be. The elephant really does have a trunk. The person perceiving it as a snake is partially correct, in having apprehended that particular dimension of the nature of reality. If a person who grasped the leg or the ear or the tusk of the elephant said it was like a snake that person would be incorrect. Their concepts would not cohere with the experience they were attempting to describe.

Jain philosophy can be seen as an attempt to systematize and render coherent what the late John Hick calls the ‘religious ambiguity of the universe.’ By this term, Hick means the fact that no particular worldview has been able to command the unanimous assent of every thinking human being. Certainly, science has been able to produce a measure of consensus regarding the nature of the physical reality which can be apprehended by the senses, a reality constantly expanding due to the increasingly refined ways in which those senses can be extended into the macroscopic and the microscopic realms. But it has not produced a consensus, even among the scientifically literate, about the deeper meaning of existence, or whether there are dimensions of reality beyond those which are amenable to scientific investigation, or what the nature of those dimensions might be. This remains the realm of religion and, of course, philosophy. One response to this situation is, as with the question of religiously motivated violence, simply to dismiss religion–to say that, if there were any truth to the teachings of the religions, they would have come to an agreement by now as to the ultimate nature and meaning of existence. This response, however, raises as many questions as it might ostensibly answer. If the religious accounts of reality are completely false, then this is, as Hick says, ‘bad news for the many.’ It means we are in a cold universe in which most people have lived lives that have been, in the words of Thomas Hobbes, “nasty, brutish, and short,” who have suffered tremendous sorrows and injustices with no hope of experiencing a better state. Now, the fact that a worldview is depressing, and demotivating does not mean it is necessarily false. It is often the case that the universe does not give us what we want, at least not immediately. This conclusion, though, does lead to a particularly difficult version of the question, ‘Why bother with anything at all?’ This is not an unanswerable question. My point is simply that it is not obvious that dispensing with religion altogether addresses our concerns in an adequate way.

Another response to the religious ambiguity of the universe is to cling tenaciously to one particular picture of reality and deny the rest. In fact, the rejection of religious accounts of reality in favor of a materialist view is itself, arguably, a species of this response: one view is correct, and the others are false.

This approach, however, also raises more questions and concerns than it addresses. First, there is the question of how to decide which model of reality is the true one, out of all of the many options available. Accompanying this is the epistemic question of how one would recognize the true view in the first place. Whatever criteria one would use would inevitably be shaped by the particular cultural location in which one would find oneself. As Hick, again, puts it very well, had I been born in Saudi Arabia, I would likely believe that Sunni Islam presented the true picture of reality; but had I been born in Thailand, I would likely feel as strongly that Theravāda Buddhism was the truth.

This leaves us, then, with pluralism: the view that all these traditions capture some aspects of reality and failure to capture others. The world’s belief systems are not the same. They differ in many important ways. They also overlap in some respects (such as the aforementioned Golden Rule). Might we respond to the religious ambiguity of the universe by delving into what all these traditions have to say and see how they might be integrated to form a more complete picture of the nature of reality? This approach is well described by Pravrajika Vrajaprana, of the Ramakrishna tradition:

The world’s spiritual traditions are like different pieces in a giant jigsaw puzzle: each piece is different, and each piece is essential to complete the whole picture. Each piece is to be honored and respected while holding firm to our own particular piece of the puzzle. We can deepen our own spirituality and learn about our own tradition by studying other faiths. Just as importantly, by studying our own tradition well, we are better able to appreciate the truth in other traditions.7

The Jain philosophy of relativity can be seen as a methodology for this process of exploring and integrating the religions and philosophies of the world into a more comprehensive picture. It is possible this process will be never-ending. To claim one has completed it fully would be to fall into the dogmatic error of asserting the truth of one worldview alone. But it can be progressive.

In other words, one can advance closer to truth in what Alfred North Whitehead calls an “asymptotic approach,” mindful that reality is always more than what our words and concepts can comprehend fully, but also avoiding the nihilistic skepticism involved in claiming they are unable to express the nature of reality at all. This could be seen as a ‘middle path’ between the extremes of absolutism or dogmatism and radical relativism.

Does one need to be a Jain to apply the Jain philosophy of relativity in the way in which I have described? Certainly, this approach to the diversity of worldviews has emerged from out of a specific worldview, a specific picture of reality. Also, historically, this philosophy was often not utilized in the way that I am proposing, but as a polemical tool for demonstrating that the Jain view was more comprehensive than its competitors (although there were also thinkers who did utilize it in very much this way).

I would suggest that anyone, beginning with any worldview as a starting point, might begin to approach the claims of other worldviews using the Jain method, assuming that each view is, in one sense true, in another sense false, in another sense both true and false, in another sense neither, or inexpressible, and so on. It would also be a good introspective exercise to apply this method to one’s own views as well, seeing where one might have insight and where one’s vision might be incomplete. In the words of Sri Ramakrishna, all religious beliefs systems are “a mix of sand and sugar.” One must utilize one’s critical capacities, in conjunction with what one already knows and understands, in order to sift out the truth from that which is a misinterpretation, or whose truth is only a function of a particular time and place and may no longer be applicable.

Mahātma Gandhi, a Hindu, found the Jain approach to difference enabled him to approach those with views different from his own with greater empathy. In an editorial in his journal, Young India, he once responded to a question from a reader who had observed that sometimes Gandhi appeared to be speaking from the point of view of the non-dualistic Advaita Vedānta tradition and other times from a more dualistic Vaiṣṇava point of view. Asking which of these philosophies Gandhi actually observed, he replied:

I am an advaitist and yet I can support Dvaitism (dualism). The world is changing every moment, and is therefore unreal, it has no permanent existence. But though it is constantly changing, it has a something about it which persists, and it is therefore to that extent real. I have therefore no objection to calling it real and unreal, and thus being called an Anekanta- vadi or a Syadvadi. But my Syadvada is not the syadvada of the learned, it is peculiarly my own…It has been my experience that I am always true from my point of view and am often wrong from the point of view of my honest critics. I know that we are both right from our respective points of view. And this knowledge saves me from attributing motives to my opponents or critics. The seven blind men who gave seven different descriptions of the elephant were all right from their respective points of view, and wrong from the point of view of one another, and right and wrong from the point of view of the man who knew the elephant. I very much like this doctrine of the manyness of reality. It is this doctrine that has taught me to judge a Musalman [Muslim] from his own standpoint and a Christian from his. Formerly I used to resent the ignorance of my opponents. Today I can love them because I am gifted with the eye to see myself as others see me and vice versa. I want to take the whole world in the embrace of my love. My anekantavad is the result of the twin doctrine of Satya and Ahimsa [truth and nonviolence].8

The Jain philosophy of infinite diversity can be of great assistance in cultivating empathy, nonviolence, and recognition of the common, fundamentally spiritual nature of every being whom we encounter, as well as a deeper appreciation for each being’s distinctive uniqueness, because it invites us to perceive a universe in which we are all participating, and yet which we each perceive in our own unique way that is appropriate to each of us at our current stage in our journey. It is a method for addressing difference which enables us to navigate the fact that our neighbors have beliefs and values different from ours (whatever those beliefs may be). We do not need to agree fully with others in order for there to be peace. But if we can value the perspective of the other as a potential source of insight into the true nature of reality, even if it is not immediately obvious how it might fit with our own understanding, our sense that the other is so radically different from us as to render communication impossible is mitigated. It enables us to value difference without compromising on our own most deeply held beliefs: to hold firmly to our own piece of the puzzle even as we realize that what we hold is only a piece, and not the whole picture.

Are there certain beliefs which are incompatible with peaceful co-existence? It seems the real difficulty of my proposal is that it requires anyone who might take it up first to accept the ever unfolding, incomplete, non-absolute nature of their own worldview. This is precisely what many religions reject, and this rejection is what many take to define religious adherence, and so prompts them to reject religion.

Many find dogmatic absolutism comforting. Even those who may not be comfortable with it may believe that to question it is to be unfaithful to their tradition. It seems to me, though, that the logic of at least some forms of religious absolutism–those which are coupled with a mandate to spread their beliefs to others–are a recipe for inter-religious conflict. Such beliefs have certainly played a massive role in religious conflict historically.

My exhortation to those who adhere to religious absolutism is to be attentive to the reality that even the strictest of religions have rich histories of interpretation, of humanistic intellectual inquiry into the teachings of the tradition, of ‘faith seeking understanding’–that is, theology. Even if one holds, as a central tenet of one’s religious faith, that a particular text is the word of God, it remains an open question what, precisely, that text means, and how it applies to the contemporary situation. Divine revelation is always filtered through the medium of a language, and languages require interpretation, which lends itself to a variety of possibilities. Diversity is not only inter- religious, but intra-religious. A Jain-style approach to the diversity of views can be applied first to one’s own tradition, and then perhaps extended to include other traditions as well. Similarly, the ecumenical movement of Christianity begins among Christian denominations. But it creates the conditions for, in the words of Raimon Panikkar, a ‘wider ecumenism’ that extends, potentially, to all religions, as well as to non-religious worldviews and modern science.

Conclusion

That people holding diverse worldviews ought to strive to co-exist, and that it is important to approach different beliefs in a spirit of respectful and open-minded inquiry, is not controversial, though it appears to be becoming increasingly radical in the current political climate. What Jainism lends to this conversation, in my opinion, is a particular precision and a powerful logic which demonstrates that pluralism need not be simply a platitude–a nice, politically correct sentiment– but can in fact be major contributor to understanding on a global scale; for here we have a model of knowledge unfolding through an ongoing dialogue among worldviews, each integrating the best of the others into itself, perhaps all one day converging in a shared, multifaceted vision of truth.

Curtesy : Original version is available from the publisher at: http://gtu.academia.edu/bjrt

- Cited in Glyn Richards, A Sourcebook of Modern Hinduism, pp. 156, 157

- Swami Nikhilananda, trans. The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna p. 60

- Cited in Richards, p. 65

- Swami Vivekananda, “Response to Welcome at the World’s Parliament of Religions, Chicago, 11th September 1893,” Complete Works, Volume One, p. 4

- Bhagavad Gītā: As It Is, with translation and commentary by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1972), pp. 21-24. The original verses are Bhagavad Gītā 2:11-13.

- Translation by Matilal. Quoted from Bimal Krishna Matilal, Anekāntavāda: The Central Philosophy of Jainism (Allahabad, L.D. Institute of Indology, 1981), p. 19.

- Pravrajika Vrajaprana, Vedanta: A Simple Introduction (Hollywood, CA: Vedanta Press, 1999), p. 56-57.

- Mohandas K. Gandhi, The Story of My Experiments with Truth (Boston: Beacon Press, 1957), p. 89.

About Author

- PhD, 2000, University of Chicago

- MA, 1993, University of Chicago

- BA, 1991, University of Notre Dame

Dr. Jeffery D. Long, Professor of Religion and Asian Studies, specializes in the religions and philosophies of India. He is the author of several books and numerous articles, as well the editor of the series Explorations in Indic Traditions for Lexington Books. In 2018, he received the Hindu American Foundation’s Dharma Seva Award for his ongoing efforts to promote more accurate and culturally sensitive portrayals of Indic traditions in the American educational system and popular media. He has spoken in numerous venues, both national and international, including Princeton University, Yale University, the University of Chicago, and Jawaharlal Nehru University (in India), and has given three talks at the United Nations.