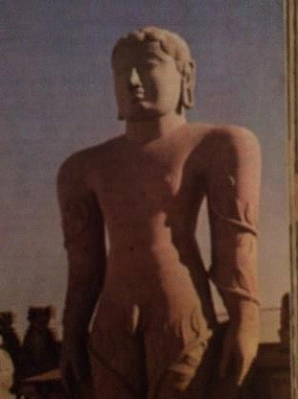

In 2015, the Archaeological Survey of India brought to light 5 temple Jain complexes, Nishidhis, sculptures, and monasteries (Govind 2015). Here are two hills, on the Sravana Betta is the figure of Bahubali, about 13 ft. in height, while on the Chikkabetta, small hill or Kanakagiri within temple precincts are the Tirthankaras, particularly Mahavira (and very miniature bas – reliefs depicting the Jain Tirthankaras, Adinatha, Suparsvanath on the rocks, on the riverbed. The date of Artipura has been established at 918 CE, while that of Sravana Belagola sculpture sis 983 CE, which allows us to deduce that experimentation regarding the carving of a monolithic sculpture took place. This was within the paradigm of separation of Bahubali and the Tirthankaras, while the monks stayed in the smaller hill, within monasteries with images of Tirthankaras – both in relief on rocks as well as in the precincts in temples. This substantiates the separateness of the function of images for monks, and the power of the living monks during the contemporary period. Adjacent to the temples, were the Jain monasteries, found in Arthipura. At Sravana Belagola, there is not much of remains of substantial monasteries, but merely a mention of, Naviluru saṅgha, a prominent Jain congregation. Jain monasteries or maṭhas that date from 5th C CE were moving educational institutions and except for staying in one place during the rainy season (varṣākāla), monks were wanderers. The existence of Jain saṅgha or gaṇa and Gacchas is attested by the one in Kitturu I in 7th C, such as Kirtisenamuni (740 CE) disciple of Amitasena Acharya (700 CE ) who was forerunner of Kitturu saṅgha. But Jain maṭhas or monasteries played a key role in the promotion of learning and public education and centered around the celibate learned cleric (who formed the pivotal figure in early medieval times). It is probable that during the 10th C, the functions and ideals of the two institutions, temple and maṭha were separated: the monastery being for meditation and temple for gathering and worship. However, the maṇḍapa could have taken over the function of meditation (as meditation on death was considered significant) while the temple was resting places or gathering spaces for talks by monks.

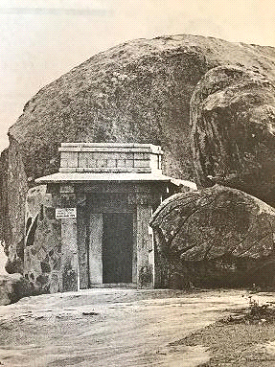

From 10th C CE onwards numerous temples were established at the site. With the growth of pilgrimage, the site began to acquire new meaning. On the Chandragiri hill are 13 temples, such as the Santinatha basti, Suparsvanatha basti, Parsvanatha basti, Kattale basti, Chandragupta basti, Chandraprabha basti, Chavundaraya basti, Sasana basti, Majjigana basti, Eradu-katte basti, Savatigandavarana basti, Terina basti, Santisvara basti, all built between 9th and 12th C CE., although, the earliest one can be dated to 8th C CE. On the Vindhyagiri were the Siddhara basti, Chennanna basti, Odegal basti, and Chauvisa Tirthankara basti. A conglomeration of basadis was not uncommnon. In Koppla, there were 772 basadsis, while Gulbarga had 700 shrines. These were also called, caityalayas and Jinalayas. These are modest in size, Dravidian in style, consisting of a sanctum or garbhagṛha, a vestibule or āntarāla, a main hall, some with front halls or navaraṅga (or mukha maṇḍapa), portico or maṇḍapa, while the sanctum is surmounted by a śīkara and the entire temple by an enclosure or suttalay or parisūtra. Jain temples have a free-standing pillar, called manastambhas facing the 4 directions, called caumukha jinas found on the top of manasthambas.

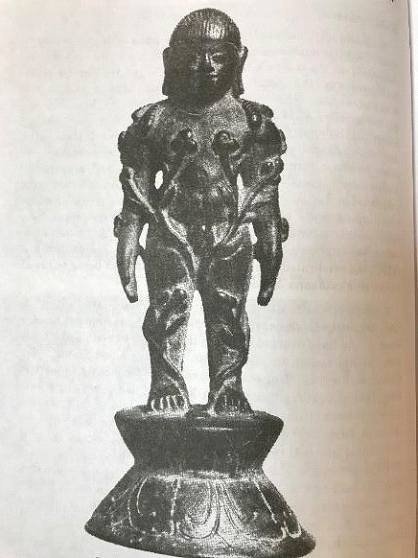

The basadis were centers of worship, evidenced from the icons of Tirthankaras or Yakṣas and Ambikās and information regarding the lighting of lamps. By this time, Jaina Canonical texts and Puranas, such as the Puraramarthprakasa, and Padmapurana of Ravisena, it was a center of ritual and festive occasions, with dance and music, attested by the epigraphical evidence from Sravana Belagola that mention them as nrittalaya or dancing hall constructed by a setti in front of the Nagara Nimalaya and that dancing halls were attached to Jain monasteries. They were centers of learning and Ghatikasthanas (educational centers) were near Jain temples, such as in Pulige (Purikaranagara), and Lakshmesvara. The Svadavada waves of doctrines, being taught in Kannada, had spread all over Karnataka, and epicenters of Jain saṅgha existed in Hombuja, Hallur, Pulie, Annigeri, Adur. They were centers of congregation for the people, who could listen to the doctrines of Jainism, in a precinct established by the monk. It is well known that Jains followed the fourfold congregation or chaturvidha saṅgha of ourfold community of Munis (male ascetics), Āryikā (female ascetics), Śrāvaka (laymen), and Śrāvikā (laywomen).

Dictated by both functionality and design, they perhaps had an economic function as well. They were centers of gifting as recorded in inscriptions. Here stone workers, particularly the śreṇī of guild of Aiyyavole 500, who had probably migrated from Aihole, center of Chalukyan School of Art was employed here. The basadis acted as employers, regulating the guild systems (trade guilds, and stone worker’s guilds). Its charities were tied to that of kings (and traders), who could now re-affirm his position as protector of religion (or dharma). However, the role of the Jain monk teacher, with his routine pious life, was admired and honored in society. They won over generals, feudal chiefs, governors, traders, Banajigas, or middle class. The monk was the inspiration behind it, who kept alive the values of Jainism, through collective and individual ritual and congregation. Thus, architecture had a social role to play and strengthened and reinforced and renewed religious convictions, provided a religious identity to the Jain community (Weder, 2016).

Regarding temple design, and in terms of adopting a mandapa style of architecture, the Jains adopted the popular design as seen in Aihole and Badami. In addition, Pandyas, and Gangas were followers of Jainism. The architect did not spend designing a particular type of building; he was not a developer, but an adaptor. Temple Architecture had been standardized in terms of space and time, it had a consistency of design, with a traditional place in society. Its form had been established, popular and ubiquitous, and multifunctional and provided a space for community exchange. In addition, the basadis elicited charity, place of learning, of ascetic practice, worship and a safe place for women. They consisted of open mandapas in addition to free standing mandapas on the hill. Mandapas and temples were functional; they were shelters from the sun and were sculpturesque than gigantic in proportion. They did not interfere or dominate the environment or even come in the way of visual emphasis, or block the sight of the gigantic sculpture, and were not solid in form. Each did not interfere with the other and there was no clash of architecture and sculpture.

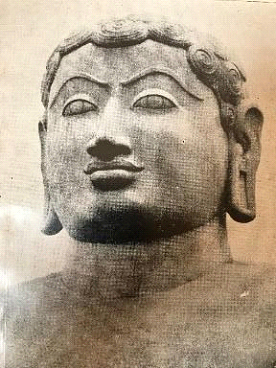

This was because there is no center of gravity at the site of Sravana Belagola. Architectural elements were designed with the aid of ‘Gestalt psychology’ that understand that the human mind is structure to perceive the environment in a way that organizes through visual field into distinct and related parts. They pursued simplified forms and spatial design. There is no central axis except when going up the hill towards the colossal figure where you find a sequence of spaces and signs and symbols. The temples are interwoven with their surroundings: the natural environment, and built ones, small open mandapas and pillars. In addition, the ordering of structures was followed a high degree of clarity and adjacency. There was no building program, but a proximity diagram of the groupings can be found. This was achieved by the manipulation of space and their location, particularly on the hills. The hilltops were considered suitable sites for Jain shrines and seats of penance for sages, which was used advantageously by the chiseling of the rock-cut dramatic, solitary majestic, serene figure of Bahubali. The magnitude of the sculpture is greater than that of architecture, as the Indian śilpī was trained in both types of art. The boundaries of sculpture and architecture are blurred; both embody a sensory experience. In addition, communication through images were embedded in India visual culture. Sculpture offered an approachable road to Jain philosophy and religious beliefs and what more could be more liberating than being on open ground with no boundaries. While temples were in the form of caves, the monolith was in the form of a Jain monk, whose ideology was liberation. Both the living monk and the statue of Gommatesvara brought the community into contact with the natural world through a (image) of Jain ideals that hovered high above them. The power and role of sculpture and architecture in building social connections and psycho-social well-being learned from the monks, was a contributive aspect of the sacred site of Sravana Belagola.

The sacredness proliferated into the landscape, stone, and hearts and imparted a community identity, and social connectivity that became a part of Jain culture.

Bibliography

Shah, Umakant Premanand. 1955. Studies in Jaina Art. Jain Cultural Research Society. Banaras Cort, John, E. 2001. Jains in the World. Oxford University Press. Dundas, Paul, 1992. The Jains. Routleledge, London.

Epigraphia Carnatica, Vol II, No . 1,

Hampana, Kamala.1985. Jainism in Karnataka. In Avalokana: A Compendium on Karnataka Heritage. Edited by H. S. Kirshnaswamy Iyengar. Directorate of Kannada and Culture. (156-160).

Indian Antiquary, Vol. 2. Jain Inscriptions at Sravanabelagola. 265- 266.

Iyengar, H. S. Kirshnaswamy. 1985. Avalokana: A Compendium on Karnataka’s Heritage.

Directorate of Kannada and Culture, Bangalore.

Jaini, S Padmanabh. 2006. The Jain Path of Purification. Univ. of Ca press, Berkeley. 1979.

Motilal Banarasidas, Delhi.

Jawaharlal, G. 2006. Studies in Jainism as Gleaned from Archaeological Sources. Harman Publishing House, New Delhi.

Lerner and Kossak. 1991. The Lotus Transcendent. Museum of Modern Art.Abrams. Nagarajaiah, Hampa.1999 Jina Parsva Temples. Sravanabelagola.

2005. Bahubali and Badami Calukyas. SDJMI Managing Committee. Shravanabelagola. 2001. Opulent Candragiri. SDJMI Managing Committee. Sravanabelagola.

Pal, Pratapaditya. 1995. The Peaceful Liberators: Jain Art from India. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles.

Ramachandran, T.N. 1944. Jaina Monuments and Places of First-Class Importance. Chhotelal Jain, Calcutta.

Rao, Nalini: 1980. Sravanabelagola. Art Publishers of India. Bangalore.

Ritti, Srinivasa. 1985. The Ganga Period in Avalokana: A Compendium on Karnataka Heritage.

Edited by H.S . Kirshnaswamy Iyengar. Directorate of Kannada and Culture. (58-63).

Sastry, Venkatachala, T.V. 1993. An Anthology of Kannada Poems on Gommateshwara. Tr. By Venugopala Soraba. Gommateshwar Bhagaan Bahubali, Shravanabelagola. London.

Settar, S. 1981. Sravana Belgola . Ruvari. Dharwar.

Settar, S. 1968. Sravanabelagola and its Monuments. Karnataka University. Dharward.

Sitaramayya, V. 1967.Mahakavi Pampa. Popular Prakashan.

Taranath, N.S. 1985. Poet Pampa in: Avalokana: A Compendium on Karnataka’s Heritage. Ed. Iyengar, H. S. Krishnaswamy Directorate of Kannada and Culture, Bangalore. 253-258.

Weder, Adele. 2016. In Search of a Paradigm: The Social Role of Architecture. Border Crossing.

Acknowledge :

Recommended Citation

Rao, Nalini (2020) “New Perspectives on Jain Architecture and Sculpture at Sravana Belagola,”

International Journal of Indic Religions: Vol. 2 : Issue : 3 , Article 2.

Available at: https://digitalcommons.shawnee.edu/indicreligions/vol2/iss3/2