Michael Tobias: The ecological dimensions of this should be obvious, no?

Shri Chitrabhanuji: Michael, Jain dharma encourages sensitivity towards not just human beings but all sentient life forms, which includes animals and plants – even single-celled beings. Every living being wants to live. You can see this in their actions and behavior. Even if you try to trap a small ant, it will try to run away. All life moves towards safety and away from danger. So, for a Jain, since it may not be possible to eradicate all forms of violence, the emphasis is on minimizing violence to all beings wherever possible. Thus, anyone who is Jain is also automatically an environmentalist and ecologist.

Michael Tobias: The concept of “minimizing violence” is, of course, a brilliant philosophical stroke, because it not only references inherently the notion of pragmatic idealism, but also invokes the goal of symbiosis, of mutual respect, empathy and tolerance.

Shri Chitrabhanuji: The symbiotic nature of non-violence and plurality of perspectives in Jain dharma has greatly inspired Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violence movement. Through Gandhi, the emphasis on non-violence has influenced both Martin Luther King, Jr. and Nelson Mandela in their freedom struggles. So you can see how the core teachings of Jain dharma have trickled into our modern world in a profound way.

Michael Tobias: The world can be brutal; and for many billions of animals and hundreds of millions of people, it is indeed so. For so many who are hurting, unemployed, desperate, and more than a billion people who are hungry, what can Jain dharma contribute?

Shri Chitrabhanuji: This is a good question and highly relevant today. The answer is subtle. The Jain notion of non-violence begins with one’s self and moves outwards to others. The violence we see in the world is a secondary violence. The primary violence is experienced first by and upon the person committing the violence. A matchstick cannot burn something else without burning its own head, first.

Michael Tobias: Very true.

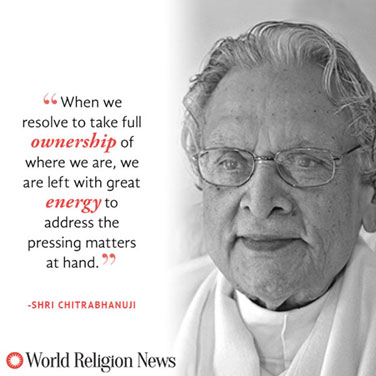

“In desperate times particularly, we should not spend our precious energy in blame or anger upon others.”Shri Chitrabhanuji: For someone who is going through troubled times, often the first reaction is anger and blame. Jain dharma teaches us that the first thing to do is to accept that “this is my situation, my karma” – what I have sown somewhere else, that is what I am witnessing here today. However, the future is wide open. It may be shaped by my past but it’s dominant influence is my present – and my present is something that I fully control. Therefore, in desperate times particularly, we should not spend our precious energy in blame or anger upon others. Our anger will likely not hurt the other but will certainly damage our own creativity and initiative. When we resolve to take full ownership of where we are, we are left with great energy to address the pressing matters at hand.

Michael Tobias: But then what?

Shri Chitrabhanuji: So if an educated person is looking to earn money and the only job s/he can find is to wash dishes – what should that person do? Focus on what you can learn from your challenge – to treat it as an opportunity for growth – to treat with dignity whatever work or opportunity comes your way. Perhaps, for a certain phase a person may not be able to enjoy the standard of life s/he desires. But there is much they can still do. I am always inspired by Edward Hale, the American prodigy and clergyman who once said, “I am only one, but still I am one. I cannot do everything, but still I can do something; and because I cannot do everything, I will not refuse to do something that I can do.” So the energy which is burnt in blaming others is applied to fulfilling one’s needs and for growth.

Michael Tobias: That’s quite compelling. Now: Is there such a thing as “Jain economics” and if so – how can it help inform a more sustainable future?

Shri Chitrabhanuji: Jain dharma embraces the notion of “simplicity” (Aparigraha) as an elegant formula for a happy life. Simple is beautiful, and a simple life is a life we can handle. Beyond a point, accumulation of things, be it money or material objects, creates complexity. Managing this complexity can rob us of the very joy that our accumulation should have provided. I have seen closely the misery that wealth can bring to individuals and families, as well as the joy and happiness accompanied by a simple lifestyle. Doesn’t modern research on happiness also find that beyond a point of necessity, money does not dramatically alter one’s level of happiness?

Michael Tobias: Clearly, every major religious and spiritual tradition suggests that accumulations are, ultimately, ephemeral. One is reminded of the poet Percy Shelley’s remarkable lines from his “Ozymandias:”

“My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings/

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!/ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay/ Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare/

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Shri Chitrabhanuji: Accumulate to be able to manage one’s life peacefully rather than to satisfy pride and vanity. It is like the man who asked “Why should I work so hard, if, at the end of it all, all I really want to do is spend time with my family in the evenings and celebrate each day?” What you want to do at the end, why not do at the start?

Michael Tobias: And so how should people going to work each morning think about notions like creating a lifestyle and future for themselves and their families?

“We should aspire to create a simple and sustainable lifestyle that meets our need but not necessarily our greed.” Shri Chitrabhanuji: We should aspire to create a simple and sustainable lifestyle that meets our need but not necessarily our greed. The purpose of life is not to enter a competition and spend life saying I want to become “like him or her.” This approach is often misunderstood as undermining enterprise and initiative. No. We should all strive to be the best version of ourselves as possible and contribute to the world as much as we can. Each person must set their own boundaries. However, in the pursuit of our aspirations, we should be mindful of the price we are paying on our personal well-being and relationships with others.

Michael Tobias: Is there a Jain “mantra of simplicity?”

Shri Chitrabhanuji: The mantra of simplicity has a lot to offer our debt-ridden world where our needs and desires often out-pace our bank accounts. If we can balance the scales a bit and find more joy in simplicity, a culture can become a savings-society rather than an indebted one. This would create a path to building a sustainable and solid foundation for our children and the community’s future.

Michael Tobias: Speaking of sustainability, which most rational people are thinking about these days – ecologically, economically, politically – do Jains get involved with politics, and if so, could you characterize just a few of the leading points of view that best suggest the key Jain precepts for community life, especially with “sustainability” in mind?

Shri Chitrabhanuji: The main precept for community life amongst Jains is the notion that all life is bound together by mutual support and interdependence (“Paraspar Upagraho Jivanam”). So, in Jain dharma, one does not aspire to “politics.” One aspires to “serve.” The difference is important. And within politics is also embedded the acceptability of competition and defeat. This is a form of violence. So, for Jains, the primary intention is of utmost importance. Is the intention to defeat someone else, or, rather, to serve by bringing out the best from one’s own self? Working with this clarity, a Jain can pursue any cause or mission that is worthwhile for society.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!