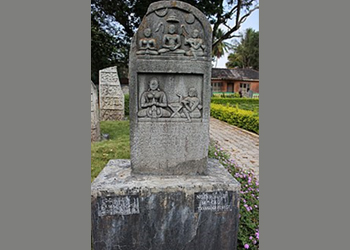

Nishidhi, a 14th-century memorial stone depicting the observance of the vow of Sallekhana with old Kannada inscription. Found at Tavanandi forest, Karnataka, India.

Jainavenue is a medium to serve the spiritual path of Jainism

The confrontation of Jain piety with the “modern, rational” secular law has made for a robust and dominant framing for current scholarly discourse about santhara, and an intriguing one. The sociological context and background for study of santhara, however, is largely reliant on the seminal but dated work of ‘Śreyas’ D. S. Baya, whose Samādhimaraṇa: Death with Equanimity: The Pursuit of Immortality was published in 2007. In addition to gathering a timeless and comprehensive collection of doctrinal references to the fast until death, Baya also conducted a more synchronic survey of media reports of deaths by sallekhana between 1994 and 2003, extrapolating from this the most widely quoted figure for estimated annual cases (about 240 annually). In the years since, local publications have put forth higher numbers, the highest being Babulal Jain Ujjwal’s estimate from 2009 at 550 (quoted in Sethi 2019). Uncertain numbers and dated archival analysis aside2, the court transcripts themselves reveal a protest: the lack of contemporary ‘field study’ to understand santhara as it unfolds, embedded in forms of sociality that cannot be assumed, and in recognition of its context and meaning.

My doctoral dissertation work as a PhD candidate in anthropology is intended to provide something of a response to this appeal. Using the methods of fieldwork and ethnography, anthropologists usually delve deeply into the lives and experiences of the anthropologist’s “subjects” or interlocutors for such insights, frequently through collecting life stories through extended interviews, relying on the genre of personal testimony. My research is a study of santhara, with particular attention to questions of, ethics and agency in everyday household and family life. I was fortunate to encounter tremendous openness, generosity, and warmth in various Jain communities in Jaipur, Haryana and Mumbai during the 15 months I was in India conducting my doctoral fieldwork from 2019- 2020.

While I sought in my fieldwork to encounter and listen to the voices of those who were undertaking santhara, by the nature of the practice, I often found myself entering a scene in which it was impossible to have much direct interaction with the fasting person. Even when I learned about a santhara in process days or even weeks before death, approaching someone who had vowed to withdraw from the world and who was therefore disinclined or unable to speak created a distinctive challenge: to remain mindful of how meaning is corporeally located in the body of the fasting person, whose soul sustains an unwavering ascetic process of bodily dissolution in the revered fast; while at the same time noting that the creation and maintenance of significance of this person’s dying is mediated at all times by the involvement and expressions of kin, monks and nuns, visitors, and the broader Jain community. This was especially true for instances of santhara among householders, particularly in Swetambar sects where the fasting person did not take diksha and depart from the home, as is compulsory among Digambar Jains. Even when I learned of a santhara after the fast was complete and attended only the palkhi, I was able to observe and appreciate a great deal about the intimate social worlds in which santhara remains the vision of an ideal death. The same way that a family might gather to lift and carry the palanquin to the cremation ground, family members often sought to uplift their relation’s state of mind as they withstood the harrowing but exalted process of santhara.

Photo credit thanks to Sanjay and Rohit Rupani

Womanhood, motherhood, and narratives of ideality

Baya’s sociological work affirms a common assertion: that among lay practitioners who undertake santhara, women do so more frequently than men. Santhara is definitively not a “women’s” practice; both men and women undertake the fast, and religious texts almost universally refer to a default male practitioner, whether muni or shravak. Yet much of the anxiety expressed around santhara in litigation is related to the fact that it presents the case of a woman who’s fast was presumed to be coerced and bore the burden of the Indian state’s protectionist stance against self-destruction, reinforced by efforts to eradicate coerced killing of women in the name of tradition, as with sati or widow-burning. Self-extinguishing deaths of women, particularly in the register of renunciation or abandonment of the world, are cast with the defensiveness of a state pushing for social restructuring of Indian society toward what are seen as modern values. Analyzing gender in the practice of santhara cannot be placed broadly within the same “grid” of religious, ideological, political, and material interests (Sethi 2019) that motivated the abolition of sati. Neither, however, can gender be dismissed or subsumed into a straightforward picture of cultural reproduction.

Perhaps it is not surprising that ethnographic study of practices of renunciation among Jain women has focused on sadhvis (Sethi 2008; Khandelwal 2004; Vallely 2002; Shanta 1997; Jaini 1979). I have sought in my research, however, to foreground reflection on feminine modes of ethical self-cultivation in Jain asceticism and in the Indian social milieu specifically in relation to the matriarchal position of elderly laywomen who undertake santhara. Among the 30 families I spoke with3 in which someone was either currently undertaking santhara or had completed their fast within a year or so, 23 were women and 7 were men. Occasionally I would ask this or that person about their thoughts on why women might undertake santhara more often than men. Many expressed the view that this was a natural development, as women are “more often at home” and “tend to be more religious and devout,” since they are largely responsible for educating children about Jainism, including a Jain diet, as well as preparing food and organizing the household’s eating habits and rhythms. At times this could be said in an offhand and dismissive manner. Other times such statements might be imbued with a sense of pride (“Women are fighters, used to work and sacrifice”) or a sense of shame or contempt (“All bad deeds come from women because they are moving around, cleaning at home; this kills more beings, so they must atone more”). Whether indifferent, beneficent, or derisive, the variety of entanglements between ideals and norms of womanhood-often conflated with motherhood-and the ideals and norms of ascetic dedication require in santhara are complex.

Some orthodox opinions hold that lay santhara is not santhara at all; or that they are inherently not ideal as compared to santhara undertaken by a saint. Similarly, some argue that santhara completed by a female cannot result in the same propitious karma as that of a male. Others have insisted that the “truth” and therefore the ideality of santhara lies in the state of mind and soul at the moment of death and that this may be, as a result of karma and/or miracles, possible for even a Jain who lived a rather lax householder life-whether male or female, with no difference. In my research, based on their demographic over representation, I tried to pay special attention to the cases of lay women who took up santhara, and particularly those whose manner of doing so appeared to embody the “ideal” form of life and death that santhara may represent.

The rendering of the saintly ascetic figure who properly undertakes the fast-meaning in the sequence laid out in scripture, and generally abiding by the requirements to obtain permission from one’s guru and family, followed by an extended period of preparation and progressively withdrawing from sustenance with abiding resolute purpose-allows for, and even mandates, the dissolution of many things before the dissolution of the body itself: worldly relations and attachments, desires; one’s sense of importance to others and oneself, one’s personhood, one’s humanness, and along with it one’s manhood or womanhood. Nonetheless, the ascetic figure is not classically a genderless one; the ascetic ideal is typically imagined as isolated and male (Khandelwal et al 2006; Banks 1997), and the figure of the woman is more often described as what is to be renounced rather than as a renouncer, despite the greater proportion of female renunciants and the predominant everyday enactment of fasting austerities (tapasya) by women in household life.

The intimate bond of motherhood and renunciation of that bond in particular carried notable emotional weight for many of the sons and daughters of women who had completed santhara-themselves adults, in many cases with grown children of their own. Watching one’s mother undertake santhara with all its heightened attention and magnitude had lingering impact, both on people’s sense of who their parent was-as a soul, a person, and a relation-and on their own sense of devotion to Jain religion. To that end I share a moving and inspiring instance in the santhara of Nirmala Shah4.

Nirmalaben’s santhara was narrated to me by her son Sanjaybhai, who began by introducing me to his mother as she was in life. “My mom was a kind-hearted lady, a social lady, very socially attached, with no big aspirations,” he told me. Immediately the story segued into the moment at which Sanjaybhai seemed to retroactively locate the beginning of his mother’s end: when she was diagnosed with a malignancy in 2015-2016. It was a shock to him and his two siblings, as she had gone to the doctor for a “normal cold and cough,” where the doctor noticed a spot on a scan of her neck and throat. They took her to a hospital in Mumbai, where she received robotic surgery and radiology, and seemed to be recovering well. After six months or so, she resumed “a normal diet, normal life”-diet and life being deeply interwoven in a particular Jain subjectivity, but also in the appraisal of a cancer patient’s state of illness or health and their prognosis; in this case (and for many contemporary santharas) the two are inseparable, compounding and reflecting the other concern. In 2019, there was a relapse, and Nirmalaben was of the view that since the malignancy had returned, she would prefer not to take any further allopathic treatment but assented to receive homeopathic and naturopathic medicine-“and end my life like that.” As her prior treatment had been effective, her children convinced her to reconsider, and an oncologist assisted them in 8 cycles of targeted chemo. The side effects were severe, and a month after finishing chemo the cancer returned.

Nirmalaben “requested [them all] with folded hands” to please stop all of the allopathic medication and treatments. Doctors had confirmed there was no other treatment for the disease, and the maximum time she had left could be four months, six months, maybe a year. “She was aware of all this,” Sanjaybhai emphasized. “There was no hiding it from her or anything like that.” Together, the family decided to let Nirmalaben live the rest of her life as she wished, and to cease treatment and take her home. As time passed, Nirmalaben found it more difficult to swallow heavy foods. “Now, here the journey starts,” Sanjaybhai told me. “And we were not aware.”

Thanks to Sanjay Shah for permission to share the above photograph.

The day came where Nirmalaben told her children that she could not swallow food any longer, so they began to arrange a liquid diet for her. Sanjaybhai’s wife offered her juices with protein powder, but after some time Nirmalaben began to decline the juices as well, reducing the quantity and saying she did not want them and couldn’t drink them. One day she said she would only take water. “That day sallekhana started,” Sanjaybhai told me. “Internally she started sallekhana….we learned after everything happened.” For thirty-three days Nirmalaben took only water and reduced the quantity gradually over time. On the thirty-third day, Sanjaybhai and his siblings all went together to their spiritual guru, whom Sanjaybhai called Majaraj sahib, who was staying at an upashray nearby to ask them what to do. They immediately came to the visit the house, climbing twelve floors to visit Nirmalaben. “So, they casually asked my mom, ‘Why are you not taking anything? Why are you denying everything?’ And she said, ‘I do not want everything. I will go to Simandhar swami and take everything in heaven.’” Sanjaybhai paused after this recollection, deep in the memory. “That means she had accepted that she will not have anything, and until the last, she was in good senses. Everything was good.”

“When Guruji came to our house he would say, santhara na bhav che? She said ‘Yes, but I cannot take.’ He asked her why, and she said because of this condition, I use air conditioning and cold water with ice. So Guruji told her that she could take santhara with the liberty of using AC and drinking cold water until evening, and not taking any after evening. Then my mom immediately told him yes I will take santhara.” They all gathered to chant the mantras, took permission from the full family, and everybody gave their permission. “The moment the chanting of the mantra started, Guruji asked, ‘Now I am giving you santhara, are you ready?’ She said yes. ‘So, I will keep the liberty to have cold water in morning, after evening you should not take it,’ but she said ‘No, I’ll not take water.’ He said he was keeping that liberty for her, and she said no. Then Guruji said ‘Now I am keeping liberty for air conditioning which you want,’ and she said ‘No, I don’t want air conditioning, I don’t want cold water. Now everything I will take at Simandhar swami’s place only and have all this. I don’t want anything.’ And she took santhara.” For the ten days after this, until she expired, she took no water at all. “And summer was there,” Sanjaybhai said, his voice in a tone of disbelief. “Temperature was 36 to 42 degrees, no wind, but she never complained or uttered one word.”

Although diksha was not given by their guru, Maasati ji, one of Maharaj sahib’s juniors, gave Nirmalaben the dress of diksha and all the pachkans “like a diksha,” and in this way she remained. Whenever Maharaj sahib and Maasati ji and the others would come to visit from the upashray, she would ask for the rajoharana, and even this Maasati ji gave to her in her last days. “She was very much aware, when she accepted this thing,” Sanjaybhai said. “She left all the attachment. While sitting, while sleeping, she remembered God only-at night also when she would wake up, whenever I would look, she was looking up, but only like this [at the image of Simandhar swami]. Opposite wall there was an image of Simandhar swami. Only like this: ay Mahavir, ay Mahavir, ay Mahavir. We observed, the last ten days, she left all attachment. She never used to look to us also. Only to her god.” On the morning that Nirmalaben completed her santhara, the family noticed that her face was grimacing; though she did not express any discomfort, the bliss and calmness that had marked her fast were gone. “At the the last moment, my wife was sitting here and one hand was in her hand, and I was having one hand. I was asking her, ‘How are you, mom? How are you, mom?’ Then Guruji came immediately and began chanting mantras and all. My mom that time was looking at Simandhar swami, and some tears came out from her eyes. Not a single word, not looking here or there, just looking at Simandhar swami.”

Thanks to Sanjay Shah for permission to share the above photograph.

“We were shocked,” Sanjaybhai said. “She never said she was thirsty, or unhappy, or in pain; nothing about her disease or feeling unwell or asking for any favor. She even digested her disease. Where her disease went, I don’t know. Otherwise, thirst-the disease will not allow you. With her inner power only…I can tell you; she has done all this one her own; she passed through the process. I think what helped her is her nature. To walk that path of santhara.” Another element of Nirmalaben’s santhara that was “shocking” to Sanjaybhai and their family was the fact that she had never fasted in her everyday life before deciding to take santhara. “She always had in her mind a guilty feeling. That always was a guilt in her mind”-that she was not able to fast for a single day, or even a half a day-if she fasted, she would vomit and become ill, throughout her lifetime. “When she fasted, she did for 43 days straight,” he said, and we both laughed, more from awe than amusement. “It was a miracle. We all could not understand.”

At another point, Sanjaybhai told me, “We all are very happy about what she has achieved. Death comes to all, and when you know that you are sure to going to die, and when you know that you are suffering with such a fatal disease, to fight with that, something that we learned from my mom, it was amazing, I cannot explain, it was amazing. To see her face, two or three days before her death, amazing. I don’t know why she was not complaining, I still don’t understand, what was there, what power was there. People usually take santhara either if they are in their last minutes of death, or when they feel that they cannot now live long; so, they feel the pain. But I don’t know why my mom didn’t feel the pain, or why she didn’t show that pain in her face. Pain must be there. I cannot agree that pain will not be there, because this disease is-you know the disease, malignancy is the most dangerous, and at the last stage, it is very, very painful. It’s very painful, but I don’t know where her pain went, don’t know what happened.”

like “We could not understand,” “I cannot explain,” and “I don’t know what happened,” were frequently uttered by family members I spoke to about santhara. Such utterances are not signs of “confusion” in a conventional sense or being unable to make sense of the situation. They reveal, rather than describe the ineffability of santhara. Many details of Nirmalaben’s fast, rare and exceptional as it was, appeared in different ways in many stories I was told during my fieldwork. The progression of a diagnosis, of failed treatment, of requesting permission and being urged by family to wait; the careful attention of those in the household who have been providing food and drink to the fasting person as they become aware of the fact that lack of appetite has been replaced by strength of will; the shocking, miraculous resolve that manifested in minds and bodies that had never shown such discipline throughout their lives-these are among recurrent features of a particular contemporary narrative of santhara, one that emerges from a contemporary urban Jain subjectivity. And certain subtleties of these markers, like the guilt that Nirmalaben felt for being unable to fast, and the pattern of first acquiescing and then slowly resisting in phases her children’s preferences about her care, further mark a kind of shadow of gender that is especially notable in the stories of matriarchs who undertake santhara.

The picture of modern santhara has not by any means abandoned the ascetic ideal as it appears in Jain orthodoxy or doctrine, which remains the “ideal ideal death”-the most ideal and the most efficacious form of death, in terms of the soul’s presumed progress toward complete moksha or liberation. Still, evidence suggests that there has been a proliferation of lay santharas since 2006. Awareness and admiration of the practice has grown, both from media attention and the concurrent rise of social media. WhatsApp groups and social media platforms have provided new forums for communal debate and learning-from hot political Twitter debates to intensive Facebook swadhyay groups. My fieldwork suggests that the enduring significance of santhara together with its “popularity” has resulted in a delicately shifting practice among lay Jains, particularly women, that has far-reaching effects within Jain families and communities. As Sanjaybhai told me, “I got closer to the religion [after being with her during that time]. Because we are businessmen, we are busy; we don’t follow so much the rigorous [practices]. After this, I got more [sic] towards my religion, my Jainism. I was so lucky, and I think that that was because of my mom’s wishes.”

My sincere thanks to the many people who have offered their counsel and confidence throughout my fieldwork, including particularly Sanjay Shah, who generously granted his permission to reproduce in this article the photographs of his mother Nirmala during her fast as well as share their story.

1 I refer to the fast in this article as santhara because that is the term used most commonly among Swetambar Jains, and the specific cases and stories which I share here are from Swetambar families.

2 My fieldwork, not yet complete, suggests numbers closer to Ujjwal’s than Baya’s. However, a major variable is what qualifies a case to be counted as santhara; the criteria for analysis following Baya is public mention, while within Jain society there may be disagreement-albeit quiet-about whether a publicly declared santhara meets certain religious or spiritual criteria to merit that distinction.

3 In Mumbai, between January and March 2020.

4 The Shah family are Sthanakvasi Jains, among whom santhara is more prevalent than other sects.

About Author

A PhD. candidate in the Department of Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, MD. Her research concerns the expression of moral agency in the Jain fast to death known as sallekhana or santhara. Mikaela’s dissertation will examine the contemporary practice of this fast, including how Jain ascetic ideals are negotiated alongside the other modes of ethical self-fashioning. Her work has been supported by the Wenner Gren Foundation and the American Institute of Indian Studies.