Definition of Sallekhanā:

“KAYA KASHAY LEKHANA ITI SALLEKHANĀ” – TO GET RID OF KAYA AND KASHAYAS IS SALLEKHANĀ.

At such time one overcomes all passions and abandons all worldly attachments by observing austerities such as gradually abstaining from food and water and simultaneously meditating on the true nature of Self until the soul parts the body.

An approximate assessment of the remaining span of life is necessary in order to adjust to the nature of fasting. One should endure all hardships, but if they fall ill or for any other reason or cannot maintain peace of mind, then they should give up Sallekhanā and resume taking food and other activities.

Accepting to perform Sallekhanā is a very special vow. The principle behind this vow is that a person while giving up their body with complete peace of mind, calmness, and patience, without any fear at all not only prevents the influx of new karmas but also purges old karmas which are attached to the soul.

Sallekhanā is also known by other names like Sanyas-marana, Samadhi-marana, etc.

This vow is not presently practiced in majority of Murtipujak sects as it is believed by them that in present time, in relation to strength of body and mind it is not suitable to observe this Vrat.

History of Sallekhanā:

Textual

The ACHARANGA SUTRA (c. 5th century BCE – c. 1st century BCE) describes three forms of practice. Early SVETAMBARA text Shravakaprajnapti notes that the practice is not limited to ascetics. The BHAGVATI SUTRA (2.1) also describes Sallekhanā in great detail, as it was observed by Skanda Katyayana, an ascetic of MAHAVIRA.

The 4th century text Ratnakaranda Sravakacara, and the Svetambara text Nava-pada-prakarana, also provide detailed descriptions. The Nava-pada-prakarana mentions seventeen methods of “voluntarily chosen death”, of which it approves only three as consistent with the teachings of Jainism. The practice is also mentioned in the 2nd century CE in poem Sirupanchamoolam.

The Panchashaka makes only a cursory mention of the practice and it is not described in Dharmabindu – both texts by HARIBHADRA (c. 5th century). In the 9th century text “ADI PURANA” by JINASENA the three forms are described. Yashastilaka by SOMADEVA (10th century) also describes this practice. Other writers like Vaddaradhane (10th century) and Lalitaghate also describe the Padapopagamana, one of its forms. Hemacandra (c. 11th century) describes it in a short passage despite his detailed coverage of the observances of householders’ Vratas (Shravakachara).

According to TATTVARTHA SUTRA “a householder willingly or voluntary adopts Sallekhanā when death is very near.” The Silappadikaram (Epic of the Anklet) by the Jain prince-turned-monk, Ilango Adigal, mentions Sallekhanā by the Jain nun, Kaundi Adigal.

Archaeological

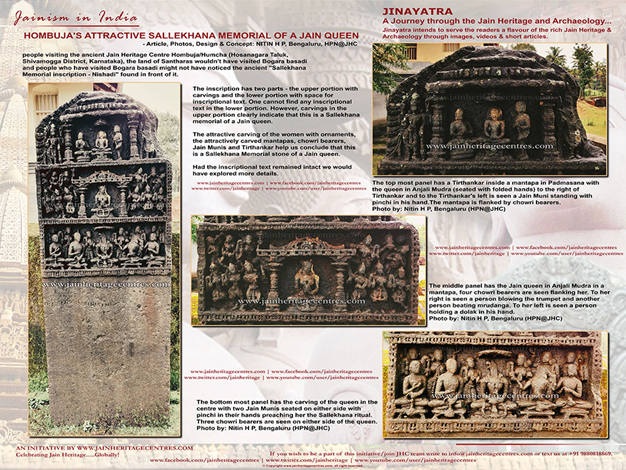

In South India, especially Karnataka, a memorial stone or footprint is erected to commemorate the death of person who observed Sallekhanā. This is known as Nishidhi, Nishidige or Nishadiga. The term is derived from the Sanskrit root Sid or Sad which means “to attain” or “waste away”.

These Nishidhis detail the names, dates, duration of the vow, and other austerities performed by the person who observed the vow. The earliest Nishidhis (6th to 8th century) mostly have an inscription on the rock without any symbols. This style continued until the 10th century when footprints were added alongside the inscription. After the 11th century, Nishidhis are inscribed on slabs or pillars with panels and symbols. These slabs or pillars were frequently erected in mandapas (pillared pavilions), near basadi (temples), or sometimes as an inscription on the door frame or pillars of the temple.

In shravanbelgola in Karnataka, ninety-three Nishidhis are found ranging from circa 6th century to 19th century. Fifty-four of them belong to the period circa 6th to 8th century. It is believed that a large number of Nishidhis at Shravanabelgola follow the earlier tradition. Several inscriptions after 600 CE record that Chandragupta Maurya (c. 300 BCE) and his teacher Bhadrabahu observed the vow atop Chandragiri Hill at Sharavnabelagola.

An undated inscription in old Kannada script is found on the Nishidhi from Doddahundi near Tirumakudalu Narsipura in Karnataka. The memorial stone has a unique depiction in frieze of the ritual death (Sallekhanā) of King Ereganga Nitimarga I (r. 853–869) of the Western Ganga dynasty. It was raised by the king’s son Satyavakya. In Shravanabelgola, the Kuge Brahmadeva pillar has a Nishidhi commemorating Marasimha, another Western Ganga king. An inscription on the pillar in front of Gandhavarna Basadi commemorates Indraraja, the grandson of the Rashtrakuta King Krishna III, who died in 982 after observing the vow.

The inscriptions in South India suggest Sallekhanā was originally an ascetic practice which later extended to Jain householders. Its importance as an ideal death in the spiritual life of householders ceased by about the 12th century.

Modern

Sallekhanā is a respected practice in the Jain Community. It has not been a “practical or general goal” among Svetambara Jains specially Murtipujaks for many years. It was revived among Digambara monks. In 1955, Acharya Shantisagar, a Digambara monk took the vow because of his inability to walk without help and his weak eye-sight. In 1999, Acharya Vidyananda another Digambar monk, took a twelve-year-long vow.

Between 1800 and 1992, at least 37 instances of Sallekhanā are recorded in Jain literature. There were 260 and 90 recorded Sallekhanā deaths among Svetambara and Digambar Jains respectively between 1993 and 2003. Statistically, Sallekhanā is undertaken both by men and women of all economic classes and among the educationally forward Jains. It is observed more often by women than men.

Types of Sallekhanā:

There are two kinds of Sallekhanā viz. 1. internal (abhyantara) and, 2. external (bahya). Out of them, the former is of passions whereas the latter is of body. The austerities which are related to subduing of the passions are called internal austerities.

Internal Sallekhanā in respect of Parinama Suddhi:

It should be noted that both the external and internal (viz. body and passions) Sallekhanā must go hand in hand. Hence, Sivarya says that the aspirant should not lose a moment without purifying the psychic states (Parinamashuddhi) while practicing body Sallekhanā.

Naturally, in respect of Sallekhanā the psychic state which affects the Self is parinama, and purifying it is parinamasuddhi, Parinamasuddhi plays basic role in Sallekhanā. In this regard, Amitgati says that the monks who practice the austerities in their excellent form without purifying the Self gain nothing but external lesya. As a consequence, stopping of the influx of karma (samvara) becomes impossible. As a result, such penance is an obstacle in the way of liberation.

The four-fold passions affect the Self. Hence, they can be called parinama. In order to purify the parinama, the passions should be subdued. The ascetic should subjugate anger by forbearance, the pride by modesty, the deceit by straightforwardness and greed by satisfaction.

Defining the term internal Sallekhanā (kasaya Sallekhanā) Sivarya says that the aspirant’s parinamavisuddhi is not possible if he is polluted by the passions. Therefore, parinamavisuddhi is called kasaya Sallekhanā. The term ‘parinamavisuddhi ‘ is related to internal possessions. In other words, parinamasuddhi is related to kashay Sallekhanā.

To sum up, the internal (kasaya) Sallekhanā is concerned with subjugating the four-fold passions, nine-fold nokasayas, four-fold sanjnas (Insticts), three-fold garvas (Pride) and three-fold inauspicious lesyas, which together come upto 23 types of internal passions.

External Sallekhanā by 6 External Penance:

Weakening the body gradually by practising the six external austerities Bahya Tapas as described in Nirjara of Nav Tattva is called external Sallekhanā. It is broadly classified into three types:

- Bhakta Pratyakhana maran: In this type there is progressive stopping of the usage of food and water.

- Ingita maran: In this type of maran there is complete avoidance of food and water.In extreme cases the sadhaka communicates through sign language. (ingita)

- Padapopagamana maran: In this type of maran the sadhaka is done in a fixed posture till the end of life.

Method to Undertake Sallekhanā:

A householder, who accepts this vow with pure mind, gives up friendship, enmity, and possessiveness. He should forgive his relatives, companions and servants or acquaintances and should ask for the pardon of all the past unpleasant deeds against them.

He should discuss honestly with his preceptor all the sins committed by him or sins, which he asked others to commit, or sins he encouraged others to commit. During the period of this vow he should eliminate from his mind all the grief, fear, regret, affection, hatred, prejudice, passions, etc., to the fullest extent.

Initially, he should gradually give up the food take liquids only and ultimately give up the liquids and take only boiled water and fast according to his capacity. He should also give up all the passions and mental weaknesses. He shall engross in the meditation without paying attention to the body. He should avoid the five transgressions. (5 aticaras).

They are:

- Ihaloga Sansappaoge: Longing for worldly reward of Sallekhanā in the next human life.

- Parloga Sansappaoge: Longing for worldly reward of Sallekhanā in next human life of dev.

- Jiviya Sansappaoge: To live longer in santhara for name and fame.

- Marana Sansappaoge: To long for early death due to intense sufferings.

- Kambhoga Sansappaoge: Longing for sensual pleasures in next life of manushya or deva as a reward to santhara.

It has been advised that to successfully observe this vow an ascetic or householder should select such a place where the government does not object to such vow and people have the respect and understanding for such decisions. This is for the precaution against disturbances or obstructions of any kind during the observance of this vow. Such a precaution is necessary to ensure the external peace and the internal tranquility during the period of the vow.

There are clear and definite directives against the adoption of the vow of Sallekhanā without realizing that the death is very near or eminent.

A classic example for this is that of Acharya Samantabhadra himself. He wished to take this vow due to the impossibility of living a life in accordance with the religious restrictions as he suffered from an incurable disease called Bhasmaroga. He approached his preceptor (guru) for the permission. His preceptor with his intuitive knowledge realized that he was going to live a longer time and he had the potential to make a very significant contribution to the Jain literature. Therefore, he declined the permission.

Sallekhanā V/S Suicide:

For many Sallekhanā is confused with suicide since the word suicide covers all self-implicated deaths. Suicide is killing oneself by the means employed by oneself. The corresponding word for suicide in Sanskrit is Atmaghata or Atmahatya (self-destruction).

Suicide is normally a misfortune of one’s own making. A victim of suicide is either a victim of his mental weakness or of external circumstances which he is not able to circumvent. In modern times, the mental and ethical strength has been deteriorating rapidly individually or in any social group. Our civilization has brought large number of psychological and social problems, which only strong individuals can survive. The disappointments and frustration in the personal life, emotional or sentimental breakdown in married life or love-affairs, unexpected and unbearable economic loss in the trade or business, sudden and heart-breaking grief due to the death of the nearest and dearest, appearance of the disease which is incurable or socially reprehensible, sudden development of depression, public disgrace or dishonor of one’s self or the family, an unexpected shock due to the failure to fulfill an ambition and many other unusual factors may be regarded, either individually or cumulatively, as causes driving an individual to commit suicide under the effect of a sudden impulse. Frequent repetitions of situations, which bring about the feelings of disappointment, depression, mental and emotional conflicts irresistibly drive the victim to the horrible step of suicide.

On the other side, in Sallekhanā none of the above psychological or sociological characteristics are found either in adopting this vow or in its fulfilment. The same way there is a big difference in the intentions, or the situations, the means adopted and the outcome of the action or its consequences.

The sole intention of the person adopting this vow is spiritual and not temporal. The adoption of the vow is preceded by purification of the mind by the conquest of all the passions by practicing for a few years.

The person adopting this vow wants to be liberated from the bondage of karma, which has been responsible for all his ills in this world, and for the cycle of rebirths in different states (Gatis). Contrary to the suicidal intention, there is no desire to put an end to life quickly by some violent or objectionable means. There is no question of escaping from any shame, frustration or emotional excitement. There is no intention to harm oneself or any member of one’s own family. The situations under which the vow should be adopted are well defined. The vow must be adopted only with the permission of the spiritual preceptor (Guru).

Sallekhanā V/S Euthanasia:

Sallekhanā is completely opposite of euthanasia.

Euthanasia is a process of deliberately ending the life to relieve someone from pain or suffering. It requires use of medicines that makes a person unconscious and then gradually kills him in this unconsciousness.

Santhara on the contrary is the process of raising one’s awareness to unparalleled heights so one may consciously experience one’s own death.

It’s not performed to relieve oneself of one’s suffering. In fact, this process increases the suffering as once commenced, the seeker stops taking even the basic medicines or pain-killers. It’s the greatest Tapas/austerity a human is capable of performing. It’s the greatest meditation, the greatest single leap a seeker can make on his journey to Godhood.

What are the means adopted towards the fulfilment of this vow?

They are not the violent means like hanging, poison, stabbing, shooting, or drowning in deep waters or jumping from a height. One must fast according to well-regulated principles. They have to increase their days of fasting gradually. They have to change from taking solid foods to liquids, ultimately giving up drinking water. One has to spend time in reading or listening to scriptures, meditation and self-introspection.

Ascetics or the learned householder can devote part of their time in preaching religion to such devotees who may be present there. They should neither hasten nor delay the death. They should wait for the natural time calmly, getting engrossed in deep meditation with complete detachment and inward concentration.

The consequence of death by Sallekhanā is neither hurtful nor sorrow to any, because before adopting this vow, all kinds of ties have been terminated with the common consent. The immediate consequence is the one of evoking reverence and faith in religion. The atmosphere around and about the dead body is the one of good venerations. There is neither sorrow nor mourning.

The occasion is treated as a religious festival with pujas, bhajans and recitation of religious mantras. There is no place for grief but there is joy. Many admire the spiritual heights reached by the departed, the calmness and peace with which death was faced and the new inspiration and devotion awakened by that supreme event.

It is impossible for each and everybody to adopt the vow of Sallekhanā because it requires the devotee to possess an unshakable conviction that the soul and the body are separate. The vow is adopted by a person who has purified his mind and body by austerity, repentance and forgiveness; has freed themselves from all the passions and the afflictions; and has ceased to have any attachment for friends and relatives. They greet death with joy, and tranquility.

Note : Digambar Sect uses the word Samadhi instead of Sallekhanā. This vow is not practiced presently by Svetambar Murtipujak sect because they say that in present era the body structure (Saghyan) is not appropriate for this kind of vow.